Module Three Overview

This week we cover a large amount of information making this the week where you will most likely want to schedule additional time to complete the work. Once you understand the concepts and searching strategies discussed this week, the other weeks should be easier because this information is the foundation of basic research. Use your time wisely this week. Do not wait until the last day to do your homework.

Lecture

Create a Research Strategy

Once you have developed your topic question (or statement) for your research project, the next step is to create a research strategy. A research strategy is a plan of action that allows you to conduct organized research rather scattered and unfocused research. Taking time to develop a strategy for your research will help you reduce frustration, enhance the quality of your research, and save you time. A research strategy consists of these steps:

Step 1: Breaking down the research question

Step 2: Identifying keywords

Step 3: Identifying alternate keywords (synonyms)

Step 4: Identifying variations in keywords (e.g. child, children, childhood)

Take the time to complete a research strategy first—before you start looking for books, articles, and websites on your topic. It helps to write your research plan on paper or using a computer.

Step 1: Breaking down the research question. Let’s take the following research question as an example: Do violent video games lead to aggression in youth? Ask yourself, what am I expected to write about? After thinking about your topic sentence, you might figure out that you are expected to write an essay on:

- Violent video games

- Teenage or youth behavior

Step 2: Identifying keywords. The next step is to identify the keywords in your topic question. These are the words or phrases you will use to search the library catalog, research databases, or World Wide Web. Your results may include items such as books, articles, and websites that contain the keywords you entered. Identify keywords—Circle the main keywords and phrases for the research question(s):

Do violent video games lead to agression in youth?

The circled words above are the main terms in the topic sentence. Using these words in a keyword search will help you retrieve relevant information on your subject:

- violent

- video games

- aggression

- youth

Step 3: Identifying alternate keywords (synonyms). Sometimes the keywords and phrases you use in a search will not produce enough information (or maybe the search produces too much information) on your research topic. If this happens, try using alternate keywords (synonyms) and phrases that have the same meaning or terms that are more broad or narrow. Broad search terms usually produce more results. Narrow search terms produce fewer results. After you list the main keywords for your topic, think about words or phrases that have the same meaning. You may need to brainstorm this step.

For the keywords and phrases above (violent, video games, aggression, youth), here are some alternate keywords or synonyms you might want to try:

Violent:

- Violence (variation on original word)

- brutal (synonym)

- cruel (synonym)

- viscous (synonym)

|

Video Games

- media (broad term)

- gaming (narrow term)

|

Aggression:

- violent behavior (synonym)

- violence (narrow term)

- hostility (synonym)

|

Youth:

- teen (narrow term)

- adolescent (narrow term)

- child (narrow term)

|

Step 4: Identifying variations in keywords. Some words can have variations, such as child, children, and childhood. Use the asterisk “*” as a placeholder for the different endings of a word. For example “child*” will search for items containing the word “child,” “children,” and “childhood.”

Some databases allow you to use a question mark “?” as a placeholder for words such as woman or women: “wom?n.” This is called a wildcard search. Another example of wildcard usage is:

Searching for "t?re" will find "tire", "tyre", "tore", etc.

IMPORTANT TIP: After completing steps 1 – 4 above, you should have a good list of keywords and phrases that you can use to start your research. As you research for information on your topic, look at your results for additional keywords and phrases you might have missed. Add these keywords and phrases to your initial list.

Searching for a Topic

A keyword search is the best place to start when researching for items on your topic.

Another type of search is called a subject search, which uses words that are chosen as subject headings. Subject headings are specifically selected words that tell you what a book or article is really about. A listing of subject headings is called a controlled vocabulary.

It is important to note that not just any word is a subject heading. Some keywords are part of a controlled vocabulary and some are not.

How do you know if the keywords that you have chosen for your research topic are also subject headings? You don’t. This is why a keyword search is the best place to start when researching for items on your topic.

Once you have started your search, you can then incorporate a subject search into your search strategy. Here’s how—

Books in the library catalog and articles in the research databases are assigned a subject heading. This is DIFFERENT than a call number, which helps you find a book on the library shelf. I will explain call numbers later in the lecture.

Remember, a subject heading will tell you what the book or article is about. Many libraries use the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) to index their books and media. There are other types of controlled vocabulary listings, but LCSH is one of the most widely used.

Two Ways to Perform a Subject Search using the Library Catalog:

1. To perform a subject search, enter words or phrases that are included in the Library of Congress Subject Headings. If you are not sure what subject headings you should use for your search, go ahead and enter your search terms in the subject search box. If the words do not match the subject headings, the library catalog will provide a cross-reference that directs you to the proper subject terms to use. The catalog may also suggest subject headings that are relevant to your search.

2. Perform a keyword search, click on a result, and look for the Subject Headings link. Clicking on the Subject link will take you to other books or articles about that subject. This technique is useful for finding other books or articles on the same subject. It can also be helpful is a resource does not provide cross referencing.

| Research topic question |

Most important keyword (s) in the research question |

Subject headings |

| What are the possible effects of tobacco use on our health? |

Tobacco, health |

Smoking - health aspects |

| Do fast food restaurants contribute to obesity in children? |

fast food, restaurants, obesity, child* |

Obesity in children |

Here are two examples of choosing keywords and subject headings:

Phrase Searching, Boolean Operators, and Truncation

Keyword and subject searches are two different types of search strategies. Other search strategies include phrase searching and using Boolean operators, wildcards, and truncation. Becoming familiar with these search strategies will help you retrieve better and more relevant results.

Phrase Searching

When using a phrase of three or more words in your search, place quotation marks around the words—for example: “physician assisted suicide.” Placing quotation marks around your phrase will allow a search tool to find these words as they appear in that order together in a result. Using the example “physician assisted suicide”, documents that have the words “physician assisted suicide” appearing next to each other in exactly that order would be included in the results.

Boolean Operators

| Search term(s) |

Will retrieve |

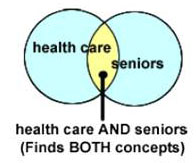

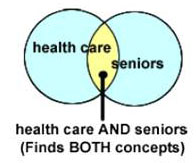

| Health care AND seniors |

All records that contain both the words "health care" and "seniors." |

The Boolean Operators AND, OR, and NOT may be included in most searches. Boolean Operators are used as connectors between words. The AND operator will retrieve results that contain all of the words or phrases used in the search. Using the AND operator will narrow your search results because all of the words must appear in the results. For example:

| Search term(s) |

Will retrieve |

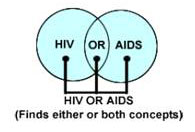

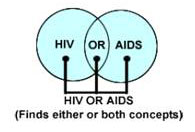

| HIV OR AIDS |

All records that contain either or both of these words |

The OR operator will find results that contain at least one of the specified words or phrases. It is generally used when you have two words that have similar meanings, such as doctor OR physician. Using the OR operator will broaden your search because only one of the words in the search could appear in the result. (Remember—OR gives you MORE because it broadens your search).

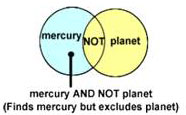

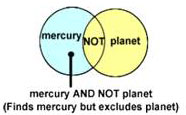

The AND NOT (sometimes just NOT) operator is used to modify the results produced by the other Boolean operators (it cannot be used by itself, you must have at least 1 other search term).

| Search term(s) |

Will retrieve |

| mercury AND NOT planet |

All records that contain the word "mercury" but do not contain the word "planet". |

Truncation (*)

A truncation sign (*) allows you to search for words with alternate endings. The asterisk will look for variations of a word ending, such as child, children, and childhood. To truncate a search term, you need to type part of the word followed by an asterisk * at the end.

| Search term(s) |

Will retrieve |

| Legal* |

legalized, legally, legalizing, legalization |

| Symph* |

symphony, symphonic |

Examples:

Wildcards (?)

A wildcard sign (?) matches any single character in the specified position in the word. For example, "anders?n" will match both "anderson" and "andersen" and “wom?n” will match both “woman” and “women.”

Not all databases will support the special search options described above or the symbols they use to perform them may be different (such as a + sign instead of AND). It is best to check the Help option in each database for more information on their particular search features and how to incorporate them into your search.

Searching the Library Catalog (YCCD Libraries):

What does every library—academic, public, school, or specialty library—have in common? They all have a way to show their users what books and other materials the library owns. This resource is usually online and is called a library catalog. (If you’re over 30, you might remember looking through a file of cards where each card corresponded to a book on the library shelves. In those days it was called the “card catalog.”)

The YCCD Libraries catalog contains records for books, media, periodicals, and some other types of materials for all of the Yuba Community College District Libraries. These libraries include Yuba College, Woodland Community College, and the Clear Lake Campus.

As part of your reading assignment for this week, you will view a tutorial on how to use the library catalog: a PowerPoint presentation I created to show you the basic search function and how to read the results.

Since all library catalogs basically function the same way, once you learn how to navigate one, you should be able to use other library catalogs as well.

Click here to view a tutorial on accessing the library catalog.

You can also download the tutorial in PowerPoint 2010 format here.

How a Book is Shelved: A Look at Call Numbers and Library Classification Systems

Once you find a book in the library catalog, the next step is to find it on the library’s shelves. Just as libraries have a way of showing their users which items they own, they also have a way of organizing the items on their shelves. This organization system uses call numbers and is called a Classification System. The two most common classification systems in the United States are the Dewey Decimal classification system and the Library of Congress classification system.

Most public libraries use the Dewey Decimal classification system while most universities and government libraries use the Library of Congress classification system. All YCCD Libraries use the Dewey Decimal classification system. Public libraries nearby also use Dewey Decimal, but CSUS, CSUC, and UC Davis use Library of Congress.

A classification system uses call numbers (letters and/or numbers) to arrange the books on the shelves. These call numbers are like an address to help people find the location of an item after they searched the library’s catalog. In theory, a good classification system should bring together everything on a particular subject, but in reality this is seldom attained. Some books deal with many subjects but are classified under the most emphasized one, so they may be shelved far away from related titles. Using a library catalog will help the library user find all the books on a particular subject.

Dewey Decimal Classification System Dewey Decimal Classification System

A nineteenth century American librarian, Melvil Dewey, was 21 years old when he developed a library subject classification system around 1872. He divided knowledge into nine classes, which he numbered 100 to 900. General works came before these under the 000 to 099 numbers. Each of the ten classes of numbers is divided further into ten sub-classes, for a total of 100, and each of the 100 by ten for a total of 1,000. By adding a decimal point and numbers after the first three digits, small subjects can be included.

The major Dewey Decimal classes are:

| 000 General Works |

400 Language |

800 Literature |

| 100 Philosophy |

500 Pure Science |

900 History |

| 200 Religion |

600 Technology |

|

| 300 Social Sciences |

700 The Arts |

|

Library of Congress Classification System Library of Congress Classification System

School libraries and public libraries use this Dewey Decimal system. It works well for small or medium sized collections. But new topics, which developed after Dewey created his system, were difficult to add. The scholarly or highly specific topics found most often in the academic libraries were also difficult to classify with the Dewey system. When the librarians at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. tried a better way, they came up with a combination of letters and numbers to create a more expandable system. A combination of letters and numbers make up the call number for placing the books on shelves by subject. The reason that automobile license plates now have both letters and numbers also applies to libraries: it makes more combinations available. The Libraries at the four year college and universities near us use the Library of Congress classification system.

One major difference between the Dewey Decimal and the Library of Congress classification systems is the way fiction (novels) and biographies are shelved. The Dewey Decimal classification system separates the fiction and biography books and places them in their own separate areas. The Library of Congress classification system does not separate fiction and biographies. Instead, fiction and biographies in a Library of Congress classification are interfiled according to their subjects. For instance, you will not find a separate Science Fiction section at a library that uses LC Classification. Those books are found within the Literature section, which the Library of Congress system designates with a "P" for the start of the call number. Individual biographies are shelved with the subject of the person. A book about Albert Einstein, for instance, is located in Physics, which the Library of Congress system designates with "QC" for the start of the call number.

Library of Congress Classifications

There are 21 letters of the alphabet used in the Library of Congress classification system. The letters not used are O, I, W, X, and Y. The letter “O” is not included because it might be confused with the number zero. The letter “I” is not included because it might be confused with the number one. The letters “W,” “X,” and “Y” are reserved for future expansion.

Main Library of Congress classes are marked with single letters. Here are the 21 main classes:

| A |

General Works |

|

M |

Music |

| B |

Philosophy, Psychology, Religion |

N |

Fine Arts |

| C |

Auxiliary Sciences of History |

P |

Language and Literature |

| D |

History (General and Old World) |

Q |

Science |

| E |

History: America |

R |

Medicine |

| F |

U.S. Local History |

S |

Agriculture |

| G |

Geography, Anthropology, Recreation and Sports |

T |

Technology |

| H |

Social Sciences |

U |

Military Science |

| J |

Political Science |

V |

Naval Science |

| K |

Law |

|

Bibliography and Libray Science |

| L |

Education |

|

A second added letter designates subdivisions. Example: PN = Literary Collections

Further subdividing is by use of numbers in ordinary sequence, starting with 1 and going as high as 9999 in some classes. Example: PN 6110 = Collections of Poetry

Decimal letters and numbers may also be used in the number area to further subdivide a subject. Example: PN 6110.H8 = Humorous Poetry

The year of publication may be added if there are later editions than the first. Example: PN 6110.H8 2006 = published in 2006

All of these elements make up what is called the call number, although it is really a combination of letters and numbers. Example: RC 662.N494 2007 is a call number for the book, The All-natural Diabetes Cookbook: The Whole Food Approach to Great Taste and Healthy Eating by Jackie Newgent.

Before looking for a book on the library shelves, you first need to determine if it is a reference book or a circulating book.

Reference books are for library use only and kept in a separate area from the circulating books. Circulating books can be checked out and removed from the library building. Most circulating books at the YCCD Libraries can be checked out for 14 days (2 weeks).

The next page will show you how to read a Library of Congress call number. It is helpful to learn how to read a call number so you can easily find it on a library shelf.

Reading Call Dewey Call Numbers

Difference between Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) and the Library of Congress Classification (LCC) System

In this lecture, I have used two sets of terminology that may sound the same but have different meanings—

1)Library of Congress Subject Headings and

2) Library of Congress Classification System.

Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) is a controlled list of vocabulary terms used to identify the different topics a book (or another type of library material) is about. There is a list because different people may use different words to describe the same topic. For example, holy space or sacred place can be used to describe those ideas. If two librarians use different phrases, then a user won’t find the library has two (or more) books on the topic. The list was created by librarians to keep subject headings consistent throughout a library’s collection. In the example used, the proper LC Subject heading is sacred space; therefore, all materials that are about a holy place would be given the LCSH of “sacred space” so all materials on that topic would come up when one searches the catalog. Subject headings are a very effective and very precise tool to find library materials.

The Library of Congress (LC) Classification System (like any classification system) is a way to give each book an address (called a call number) that is used to place materials on the same (and similar) topics next to each other on the shelf and give a library user a “address” so they can find the item quickly. The YCCD Libraries use the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) System, so it is important that you understand how the numbers work. Please review the following websites to help you understand the DDC more. There are some subtle differences in how each library uses any classification system, so don’t be surprised if you notice difference in DDC call numbers at the YCCD libraries or your local public library.

Review the following websites on how to read Dewey Decimal Call numbers.

- University Library - University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign - How to read a call number

http://www.library.illinois.edu/ugl/howdoi/callnumber.html

- Let’s Do Dewey – Middle Tennessee State University

http://frank.mtsu.edu/~vvesper/dewey2.htm

MLA Citation Format

Many instructors require you to include a list of sources with your research paper. Including these sources lets your readers know where you got your information. It also gives your readers items they could consult if they wanted to learn more about your topic.

Listing the sources used in a research paper involves using a special format, called a citation. Most students generally use one of two different citation format systems from either the Modern Language Association (MLA) or the American Psychological Association (APA). Other citation formats exist, so you may encounter a different style sometime in your college career. The MLA format is generally used in English and humanities classes, and the APA format is generally used in the social sciences and Nursing classes. Both styles have their own way of citing sources. In this class we will use the MLA formatting system – which is the most common citation method at our college.

As you gather information on your research topic, you might end up with a list of books, articles, and websites. Collecting this list of sources is useful. However, to learn more about the topic, you will need to review and take notes on each item you have gathered. This review and note-taking process helps you to learn more in-depth information about your topic. After reviewing each source, you will have a better idea about what is being said about the topic, and it will help you to formulate your own opinion about it.

A Note about MLA Format

The MLA format you will learn in this class is based upon the 7th edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers by the Modern Language Association. This is a new edition that was released in April 2009 and contains some significant changes. I expect you to submit your MLA citations in the new 7th edition format.

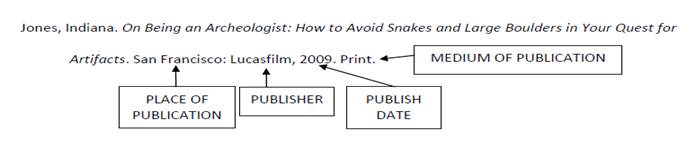

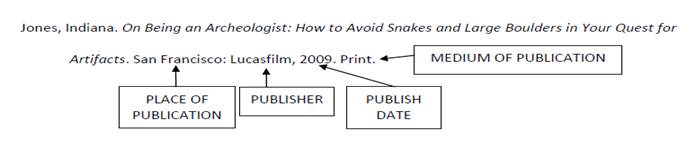

MLA Basic Format for a Print Book:

Author’s lastname, firstname. Title of book. Place of publication: Publisher, publish date. Medium of publication.

Below is an example for a book with one author using the MLA format. Notice the double spacing and one-half inch indention (five-spaces) after the first line.

The example I have given above is for a book with one author; however, books are also written by editors or more than one author. Books also come in multiple volumes or editions. For more information about how to cite books other than the example I have given, you can try these websites (right click and open in a new window):

Duke University Library:

http://library.duke.edu/research/citing/workscited/

Purdue University, MLA Format:

http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/557/15/

Documenting Sources in MLA Style: 2009 Update

http://image.mail.bfwpub.com/lib/feed1c737d6c03/m/1/Hacker_MLA2009Update.pdf

ARC Library Handout on MLA Format:

http://www.arc.losrios.edu/Documents/Library/Handouts/mla_style.pdf

| Reading |

| As part of your reading assignment for this week, view the tutorial on how to use the library catalog:

Through the learning modules, week 3, review the file titled “YCCD Catalog: Basic Search & Results”

Read the following information from your textbook (remember you may be tested on anything in the textbook):

| Topic |

3rd Edition |

4th Edition |

5th Edition |

Database Searching (Catalogs, Databases, Internet) |

Pages 17-36 |

Pages 17-32 |

Pages 53-70 |

Library Catalogs & Classification Systems |

Pages 37-48 |

Pages 33-55 |

Pages 71-89 |

Preparing a Bibliography |

Pages 148-155 |

Pages 153-162 |

Pages 135-144 |

|

| Discussion Forum Participation |

No Discussion this Week – You have enough homework already!!! |

| Graded Assignment (35 points): |

| IMPORTANT Note: For this week, you will submit your Week 3 assignment using BOTH the Assessment feature and the Assignment feature in Blackboard.

ASSESSMENT and DROPBOX INFORMATION (5 parts):

1. Part of ASSESSMENT: I will ask questions related to your reading assignment (for example: true/false, multiple choice, and/or matching questions).

2. Part of ASSESSMENT: Thinking about your research topic, I will ask you to identify two keywords, phrases, and/or synonyms you might use to find information on your topic. Use the brainstorming techniques in the Choosing a Topic tutorial (from Module 2) if you need help identifying keywords, phrases, and/or synonyms.

3. Part of ASSESSMENT: Thinking about your research topic, I will ask you to identify one Library of Congress Subject Heading connected with your topic. If a student were to look up the topic in the library catalog, what “subject headings” could they use? Remember—Library of Congress Subject Headings are specifically selected words called a controlled vocabulary. Subject Headings are the words you use to perform a SUBJECT search using a library catalog. The subject headings are different from the Library of Congress classification system (i.e. call numbers).

4. PART of ASSESSMENT: You will need to use the library catalog for this question before you start the Module 3 ASSESSMENT (Assessment) (unless you are good with multiple windows opened). A link to the library catalog is found on the the Library’s website (right click to open a new window):

http://wcc.yccd.edu/academics/library-catalog.aspx

Using your research topic along with your keywords, phrases, synonyms, and subject headings, search the library catalog for books. Start your search with a simple keyword search. Also try a keyword search related to your topic and add a reference type. For example, if you are looking for an encyclopedia on mental health, you could type the words mental health and encyclopedia in the search field. After you have done a keyword search, try a subject search using your subject headings.

Find three books on your research topic. Write down the following information. You will use this information to create your MLA citation. You will be asked for this information in the Module 3 ASSESSMENT and you will be submitting an assignment in which you cite these 3 books using MLA formatting.

Book #1:

- Name of Author(s) and/or Editor(s):

- Title of Essay or Article in Book (if an anthology):

- Title of the Book:

- Edition (if book is a second or later numbered edition or a revised edition):

- Volume Number (if any):

- Total number of volumes (if any):

- Place of Publication:

- Name of Publisher:

- Date Published:

- Page Numbers (if anthology):

- Medium of Publication (Print or Web):

What search strategies did you use to find this first book? Did you use a keyword or subject search? What words or phrases did you use?

Book #2:

- Name of Author(s) and/or Editor(s):

- Title of Essay or Article in Book (if an anthology):

- Title of the Book:

- Edition (if book is a second or later numbered edition or a revised edition):

- Volume Number (if any):

- Total number of volumes (if any):

- Place of Publication:

- Name of Publisher:

- Date Published:

- Page Numbers (if anthology):

- Medium of Publication (Print or Web):

What search strategies did you use to find this first book? Did you use a keyword or subject search? What words or phrases did you use?

Book #3:

- Name of Author(s) and/or Editor(s):

- Title of Essay or Article in Book (if an anthology):

- Title of the Book:

- Edition (if book is a second or later numbered edition or a revised edition):

- Volume Number (if any):

- Total number of volumes (if any):

- Place of Publication:

- Name of Publisher:

- Date Published:

- Page Numbers (if anthology):

- Medium of Publication (Print or Web):

What search strategies did you use to find this first book? Did you use a keyword or subject search? What words or phrases did you use?

5. Part of DROPBOX: Create MLA citations for the three books you found in the library’s catalog. Use word processing software to create your MLA citation. Include a brief, two or three sentence description of the book. Save the file and submit to the Module 3 Assignment in Blackboard.

File formats accepted: I cannot read every file format on my computer. Here are the file formats I will accept:

- .rtf = Rich Text Format – any word processing software will save a file as .rtf (Rich Text Format). This extension is the one I prefer you to use.

- Any Microsoft (MS) Word file extension

- .pdf = Portable Document File

I cannot read Works files, Word Perfect files, or Open Office files – DO NOT SEND ME FILES FROM THESE SOFTWARE PROGRAMS. Keep in mind that if I cannot open and read your homework, I cannot grade it. If you need help saving your file, ask me.

If you need help submitting the assignments, ask me. |

| Quiz (30 points) |

|

Dewey Decimal Classification System

Dewey Decimal Classification System  Library of Congress Classification System

Library of Congress Classification System